Can you really build AI unicorns in the public sector?

5: My current stance on the investment opportunities in the public sector in the new era of AI

Early-stage investors are always thinking about things like total addressable market (TAM), sales velocity, and ideal customer profiles (ICP). These are top-of-mind when evaluating any opportunity, so it’s no surprise that many are skeptical about the idea of building a $1B+ company in the public sector. The space is weighed down by archaic systems, rigid budgets, and bureaucratic sales processes that can feel impossible to navigate as a first-time (or even experienced) founder. So, who wants to bet on a unicorn here when the customer still uses fax machines in the age of AI?

Well, I’d argue that we should — for very specific reasons of course. I’ve come across enough compelling examples of companies building incredible things for the public sector, and I’ve been thinking about what patterns or principles might guide investors (and myself) evaluating this space.

The great shift of government with AI

Over the last decade, governments have started waking up to a painful truth: analog infrastructure can’t handle all the digital-era problems. From COVID-era unemployment backlogs to cybersecurity threats and system black outs, the public sector is being forced to modernize. Government agencies are also being faced with exponential amount of pressure from the trump administration to streamline their operations as a way to decrease federal deficits.

Palantir is the obvious example here, a company that’s built a multibillion-dollar business off deep government partnerships. Over 55% of its current revenue comes from government agencies ($1.57B to date). And yet, most investors still think of public sector wins as one-offs or simply too slow & political to scale.

And yet, there are a handful of companies quietly reaching real scale in the space — they just don’t look like the ones you'd see at a YC Demo Day. You’re more likely to find them buried in procurement portals than featured on TechCrunch. They serve domains like benefits disbursement, municipal finance, permitting, disaster response. This is not exactly the “sexy” markets that attract hype, but incredibly sticky once embedded.

Building a long-term moat in the Public Sector

When thinking about how these companies win, it’s useful to borrow a lens from Equal Ventures’ “capabilities before moats” framework. Before startups build defensibility, they build a capability — something that allows them to navigate complexity better than anyone else. In the case of public sector startups, I’ll argue that the most important capability isn’t scale or network effects. It’s organizational design. Specially at the seed stage, I believe this is the difference between life and death for these startups.

Why? Because selling into government is a maze. You’re dealing with fragmented decision-makers, rigid procurement rules, and compliance hurdles that would make most founders run for the hills. You don’t just need a great product — you need the right people, processes, and institutional knowledge to move through that maze repeatedly and reliably. The founders who succeed here do it by having the right people, sales strategy, and go-to-market structure that can work through red tape.

What I’ve noticed is that this makes the usual “is the product truly differentiated?” lens the wrong one because in these markets it often doesn’t take a category-defining product to win. These systems still run like it’s 1995… Sometimes, it just takes the right person to replace or improve them.

Organizational design is what lets these startups win bids, tailor solutions to different agency needs, and handle long sales cycles without burning out. It’s what helps them stay sticky once they’re in because the customer knows they understand how the system works, and how to work within it. This allows them to acquire and gatekeep contracts — and in some cases, state-granted control over key resources — in the long term.

Some of these companies eventually build scale or network capabilities too. This is especially true once they figure out repeatable deployment models across cities or states. But their edge starts with how well they’re internally designed to navigate one of the most complex go-to-market motions in tech.

How to build here in the early days?

One of the most common concerns investors raise in the early stages of public sector startups is around TAM—often framed as “how many public agencies are there?” and “what % the startup could capture”. But time and time again, we’ve seen these companies expand their TAM well beyond what was initially pitched.

They launch new products, layer on data and adjacent services, and increase customer Life-time-Value (LTV) over time. A great example is Prepared. In the early days, their TAM was likely the ~6,000 Emergency Call Centers in the U.S. Most investors likely thought, “That’s a small and price-sensitive market, can they really scale?”

Fast forward to today: Prepared has now raised over $139M and now offers 3–4 use core products tailored to its ICP, proving that product expansion and deep understanding of the public sector customer can unlock substantial upside.

Another common theme I’ve noticed: these founders spend a lot of time embedded directly where their customers are. Now remember the “forward deployment” strategy that Palantir made famous? To no one’s surprise, it just works. Many of the most successful companies in this space started with a totally different wedge product—often something unscalable or obscure—and only figured out their breakout product by being on the ground, side-by-side with their customers.

So, here is my biggest advice for founders building in public sector: grind and iterate fast, because you often get just one shot to impress the big budget decision-maker. Let’s dive deeper into the journey of some of these companies below.

Public Sector Startup Examples

Mark43

Status Quo:

Before Mark43, police departments relied on legacy, on-premises records management systems (RMS) that were slow, clunky, and error-prone — “like someone vomited a thousand bugs on a screen.” Officers routinely spent excessive time digging through nested menus and duplicate fields. Data entry took 5 times longer than necessary, bogging down critical workflows.

They have raised a total of $219M in funding over 6 rounds.

Founding Story:

The story begins in spring 2012, when Harvard students Scott Crouch, Matt Polega, and Florian (“Flo”) Mayr were assigned a class project with the Massachusetts State Police. The goal was to analyze the effectiveness of a community-based gang model using data analysis. But as they dug in, they quickly realized the real blocker wasn’t data, it was the archaic software police were forced to use.

After prototyping some social network analysis tools, they caught the interest of Torrance PD and went on to win Harvard’s President’s Innovation Challenge. Backed by a $2.2M seed round from Spark Capital, General Catalyst, and Lowercase Capital, they embedded themselves with officers: “sitting in a gang unit trailer, building, iterating.”

That hands-on work led them to Washington, D.C., where they demoed their early product. The response? “The CSI stuff is cool, but we need something that writes reports and handles arrests.” So they pivoted. Mark43 launched a modern RMS system for 10,000 officers in D.C., cutting arrest report time by 50% and offense reporting time by 80%.

Prepared

Status Quo:

Emergency call centers (PSAPs) have been stuck relying on legacy, landline-era systems—even though approximately 80% of 911 calls now originate from mobile phones. Typically, dispatchers receive nothing but voice calls, with no photos, videos, or real-time translation. This lack of context slows decision-making and increases room for error. 911 dispatchers in centers use 8-10 screens to get their work done.

They have raised $139M in funding over 6 funding rounds.

Founding Story:

Prepared was founded in 2019 in New Haven, Connecticut by Michael Chime, Dylan Gleicher, and Neal Soni. The three Yale students deeply affected by nearby school shootings at Chardon High School and Sandy Hook Elementary. Initially building solutions for school safety alerts, they quickly pivoted when they discovered the broader technical dysfunction in 911 dispatcher systems.

During a school safety pilot, the team realized that the root issue wasn't just alert systems, it was the outdated emergency response infrastructure. So they refocused to create a mobile-first, multimedia-enabled 911 platform that leverages AI, video, and real-time translation to enrich the emergency communications. The founders spent hours in PSAPs to understand the workflows and systems that dispatchers were accustomed to everyday.

Similarly, I’ve made a bet on a company building in the public sector, specifically in traffic management, which I referenced in my last blog post. It took me a while to fully grasp the complexity of stakeholders in the transportation ecosystem and I also didn’t understand the magnitude of a problem that it is to navigate this. But now, I believe the founder is uniquely positioned to navigate that landscape and change the status quo. They’re already started showing early proof points that suggest they can, which is one of the value props I saw.

Exit Transaction Comp Analysis (Liquidity!)

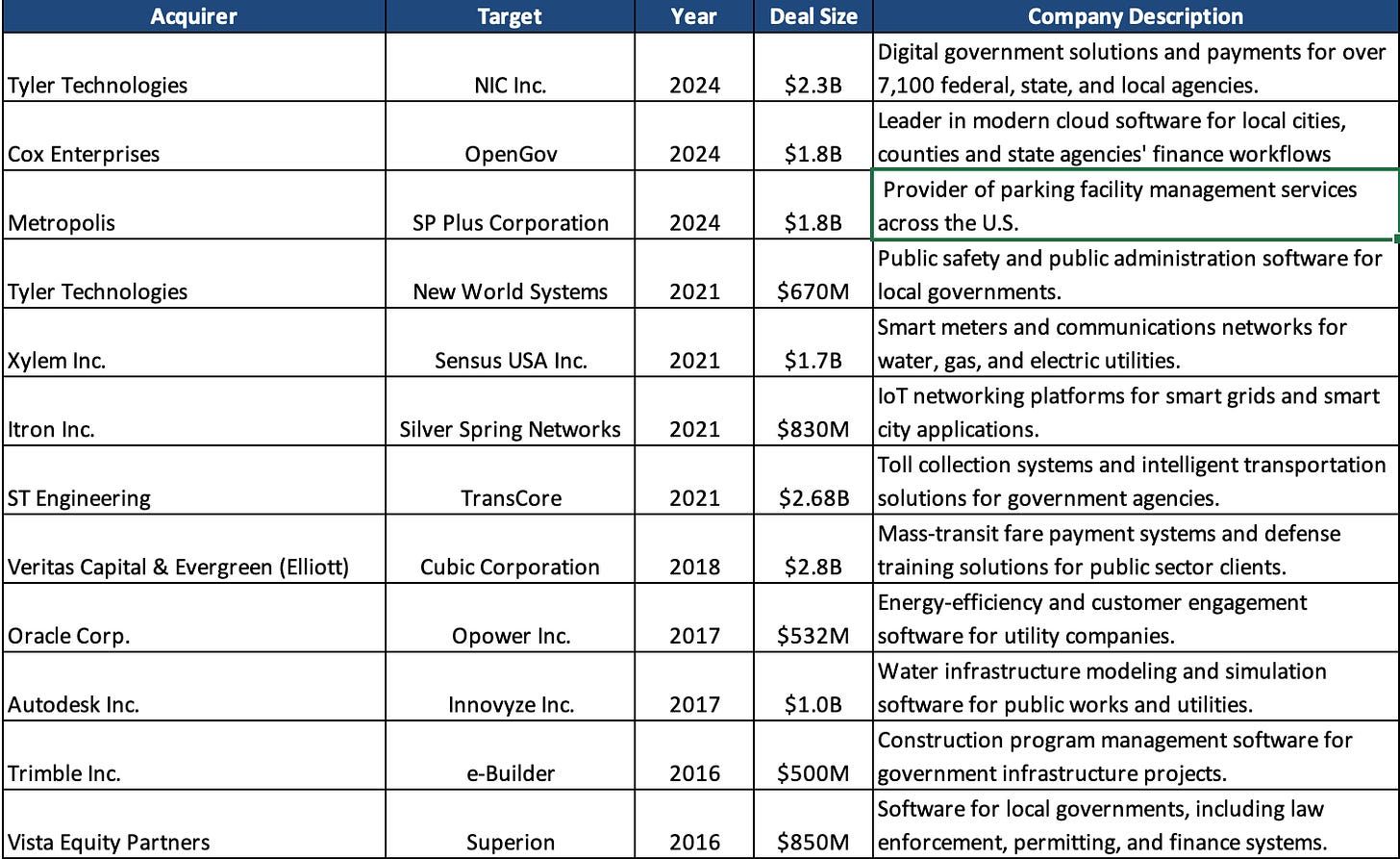

Now, let’s look at some actual exit transactions over the last 10 years that cleared $500M or more. This is important for venture investors to consider because the number of IPOs has declined sharply over the past two decades, making M&A the more likely exit path for most companies building for the public sector.

These exits range from cloud software platforms to IoT networks and infrastructure systems used by governments. From a business model perspective, most of these are pure software companies, including:

NIC Inc.

OpenGov

New World Systems

Superion

e-Builder

Opower

Innovyze

These companies built scalable SaaS solutions for government operations—ranging from permitting and budgeting to infrastructure planning and citizen engagement.

By contrast, firms like Sensus, Silver Spring Networks, TransCore, and Cubic combine hardware with software or offer infrastructure-heavy services.

Revenue Multiple Breakdown

The other missing piece for a fund manager to assess underwriting an investment here is: what valuation multiples can they expect these companies to sell for? To cut to the chase here, I do not have a full dataset to share. Business metrics are opaque when transactions are disclosed, so bare with me here.

Multiples shown below are based on enterprise value (EV) or net purchase price. However, keep in mind that revenue figures aren’t always disclosed, so valuation multiples are available only for some.

New World Systems: At ~$337 M in revenue, the $670 M acquisition equates to approximately 2.0× revenue.

Sensus: With $837 M in revenue pegged against a $1.7 B purchase, this is ~2.0× revenue, but more telling is the 10.7× EBITDA multiple.

TransCore: The transaction was completed at 16.2× EV/EBITDA, per official disclosures.

Opower: Oracle paid $532M with an EV of $487 M, representing a 3.3× EV/revenue multiple.

e‑Builder: With ~ $53M in revenue, the ~$500 M acquisition implies a steep ~9.2× revenue multiple.

In Conclusion

I’ve spent a lot of time wrestling with what it really takes to build a big business in the public sector. The usual SaaS playbook just doesn’t translate cleanly here. At scale, these companies may look similar to their private counterparts, but when you zoom in on their founding stories, GTM motions, and early lessons, it becomes clear that the path is different. I am still looking at early-stage seed companies building here, and along the way I hope to share more with you all!

That said, if you’re building in this space, I’d love to connect and hear more about what you’re trying to fix. denny@runacap.com