The Price of Progress in Venture

8: My looming thoughts on the current state of venture and what can be done today to win tomorrow

Something I’ve been seeing in the Valley is that several early-stage funds are deploying much faster than planned. Funds meant to last 30 months are getting deployed in 20-24 months. Investment teams are speeding up because they don’t want to miss the AI platform shift, and many believe the key category leaders may get decided in the next year or two.

That urgency is real, and it’s reshaping behavior across the board for both founders and investors. Alfred Lin recently described part of this phenomenon in a podcast as “the price of progress”, and it stuck with me. Building software is easier than ever now, but that ease has created far more competition. What qualified as “hard” 10 years ago is now the baseline. It feels like expectations keep rising and the bar for execution keeps moving up. This is great for society because companies continue to tackle the next set of novel problems, but it also leaves far less room for error for those involved.

Also as a compounding factor, capital is dramatically less scarce than it was a decade ago. There’s more of it than at any point in history. I think the scarce thing now is taste—the ability to recognize and solve problems in a differentiated way with 10x more competition. Accelerating factors that feed into the price of progress in venture include faster fund deployments, rising competition, and cheaper AI building tools. Theres no doubt that founders and investors are both operating in a far more competitive environment than we’ve ever seen.

The Tale of Valuations

When you look at the latest Carta data, the headline numbers suggest a booming market. But the median hides a clear split. We’re seeing one of the sharpest divergence in recent venture history.

Series A valuations are hitting new highs (median ~$48M). Investors are paying steep premiums for the handful of companies that look like “breakout” winners. Teams that either prove or convincingly signal they can cut above the rest.

Yet deal counts are down ~18%, and nearly 17% of all venture capital raised in Q2 2025 came from bridge rounds, a big jump from prior years. For companies outside the “AI breakouts” bucket, this is the price of progress. Flat or down rounds just to stay alive long enough to reach the next up round are becoming much more common now.

It seems like the top of the market is inflating, the middle is thinning, and the rest are grinding through a tougher fundraising environment than what most of what social media suggest.

Why the Middle is Getting Squeezed

Ignoring the data above, founders are undoubtedly feeling the pressure to move faster than ever. In 2021, capital was abundant for almost everyone, but it set up a harsh market correction later that both founders and investors paid for. Today, AI companies in both infra and application layer are blowing past every historical benchmark in SaaS.

Lovable reportedly hit $100M ARR in 8 months. For comparison: Wiz took ~18 months to reach that milestone; Deel took ~20.

Cursor has done the same with a fraction of the team size that would’ve been considered viable just four years ago.

On the infrastructure side, we’re seeing $200M+ seed rounds raised almost entirely on founder pedigree and track record.

Even at pre-seed, where giant rounds are less common, total cash going into rounds above $1M is higher than in 2024 according to Carta’s latest report. This is a clear sign of consolidation, where the top perceived AI teams are raising larger rounds and everyone else is raising materially smaller ones.

To many investors, the execution speed of these teams justifies the pricing. But it leaves 98% of founders wondering why their steady, linear growth no longer commands the check sizes it did 3 years ago. As I mentioned earlier, this is the price of progress in venture today.

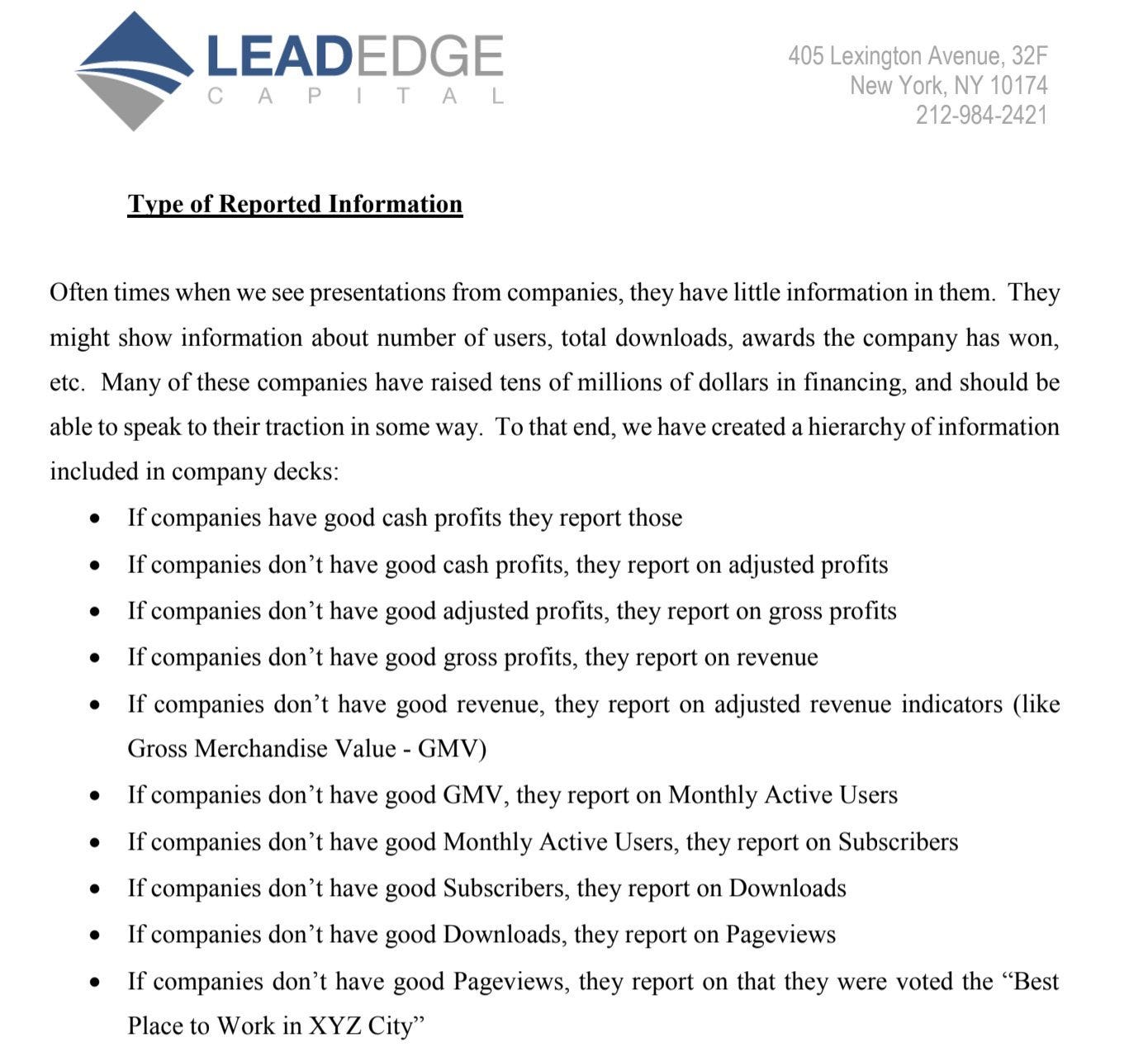

Great seed funds understand this dynamic. Their job is to partner with the best founders at inception, even if that means taking less ownership upfront because venture is a job defined by outliers. And outliers, almost by definition, have negotiation leverage. But, I want to flag that there’s been a rising phenomenon of revenue inflation. Not all revenue is created equal. Many early-stage teams are presenting “ARR” that is actually just 1–2 months of MRR multiplied by 12, sometimes padded with one-time fees. Unfortunately, I’ve seen countless pitches where the top-line numbers look impressive on a deck, but fall apart the moment you examine what’s recurring and what isn’t. Refer to the classic checklist below, its truer than ever in the age of AI:

The Hard Work Behind Non-Consensus Bets

Being contrarian is still one of the strongest forms of discipline a VC can practice in a market like this. But “discipline” doesn’t mean hoarding cash. In venture, you can:

Deploy quickly (to demonstrate activity)

Chase logos (to suggest taste)

Co-invest alongside brand name funds (to signal access)

But in the end, this is no replacement for fundamentals. In the end, venture is a human business. Before any investor talks about “adding value,” the way you show up, listen, and push founders matters more than anything else. I look for founders with a high degree of agency and a real tolerance for risk. Plenty of people are smart but far fewer have the personality and values required to navigate the chaos of company-building. And you can usually tell within the first hours of meeting them. This is also why so many people describe venture as an apprenticeship business; you build that judgment only by seeing hundreds of founders and calibrating your instincts over time. Before I defend and champion an investment to the rest of my partnership board, I need to arrive to clear conviction.

I ask myself a few questions that seem simple on the surface but are actually hard to answer without doing the work. The work includes spending time with the founder, diligencing the market, and forming a thematic view. No shortcuts.

Does the founder have urgency and the ability to pivot when their wedge proves wrong?

This usually signals whether they can attack a problem from multiple angles and iterate quickly.

Can they delegate and shift focus as the company scales?

This usually signals their ability to lead and hire.

Can they convince someone to pay?

This usually signals the market’s propensity to pay for the solution.

It’s there a clear inflection point in the market?

This usually signals a unique insight or favorable condition that makes this the right time to invest

With that being said, most outlier founders are solving problems that normal people (with normal levels of sanity) would never tolerate. Outside of AI, a lot of my time is going to founders building unglamorous but important products. Things like improving broken processes, reducing integration friction, or redesigning workflows that fundamentally change user behavior in industries most people have stopped trying to fix.

I want to iterate that not every valuable company in this era needs to be an AI company. Some of the best founders today are quietly building practical, behavior-changing products that solve real pain in places most people overlook.

The Truth behind Pivots

The trajectory of innovation is rarely a straight line. It’s usually a path shaped by failed assumptions, limited resources, and the strategic pivots that unlock what most investors call “product market fit”. I look for the factors I mentioned in the previous section because no one should underestimate the mental health implications of a founder having to let go of their initial dream. Many of today’s category leaders look nothing like their original ideas. Lets take a look at some:

Pivot: Classroom Feedback Tool (ClassStars) → Customer Data Platform

Founders originally built “ClassStars,” a tool for professors to see if students were confused during lectures, but it failed to gain traction. While building it, they wrote a small code library to route data to various analytics tools (Google Analytics, Mixpanel) simultaneously to save engineering time. They realized this internal utility was their only valuable asset, open-sourced it, and it exploded in popularity, eventually selling to Twilio for $3.2B.

Pivot: Drone Software → Collaborative Interface Design

Founder Dylan Field initially applied for the Thiel Fellowship with a pitch to build software for drones to monitor traffic and catch reckless drivers. However, after facing regulatory hurdles and privacy concerns, the team shifted focus to the power of WebGL technology. They realized they could use it to bring creative tools to the browser, pivoting to build the first professional-grade interface design tool that ran on the web. $20B+ IPO now.

Pivot: User Testing Marketplace (Opentest) → Video Messaging

The founders launched Opentest, a marketplace where companies could pay experts to record video feedback on their websites. They noticed that their customers didn’t care about the marketplace itself; they just wanted to use the simple Chrome extension the team had built to record the videos. They scrapped the marketplace entirely to focus on the recording tool, creating the category of asynchronous video messaging. $1B acquisition now.

Pivot: VR Headset (Veyond) → Corporate Cards for Startups

The founders entered YCombinator with a pitch for a virtual reality headset, despite having no hardware experience. They quickly realized they were “tourists” in the VR space but experts in payments, having previously built a payment processor in Brazil. They pivoted back to their domain expertise to solve a problem they faced personally: startups with cash in the bank couldn’t get credit cards

Pivot: Venmo for the UK (Cashew) → Internal Tool Builder

David Hsu started “Cashew,” a peer-to-peer payment app for the UK market, but struggled with low retention and brutal unit economics. While building it, he realized he spent more time coding internal admin panels to manage fraud and refunds than on the app itself. He pivoted to build a low-code platform that allows developers to build these internal tools in minutes rather than days.

Pivot: Consumer Budgeting App (Silver) → Banking API

Zach Perret and William Hockey initially set out to build a “better Mint.com” consumer app for budgeting and financial planning. They spent months just trying to scrape bank data to make the app work, realizing that the lack of infrastructure was the actual industry bottleneck. They abandoned the consumer app to package their scraping technology as an API, which now powers the entire fintech ecosystem

Pivot: Recruitment Platform (GroupTalent) → Sales Engagement

The company began as GroupTalent, a marketplace matching tech talent with employers, but they were weeks away from running out of cash. To save the business, the sales team built a scrappy internal workflow to automate their cold emails and follow-ups, which worked incredibly well. They realized other sales teams needed this workflow more than the recruiting service, pivoting to become a billion-dollar sales engagement platform.

Pivot: Voice-to-Text App (Sonalight) → Product Analytics

The founders spent years building Sonalight, a “Siri for everything” app that allowed users to text while driving. To figure out why retention was low, they built a high-performance internal analytics engine that was far superior to existing market solutions. When other startups asked to use their analytics tool instead of their app, they shut down Sonalight to launch Amplitude

A letter to founders:

I know it’s not completely obvious to founders the way VCs arrive to conviction in a decision. That’s partly why I wrote this blog post, to offer an honest perspective during this competitive market cycle. When you’re pitching a VC, remember that most investors fall into one of 3 buckets:

It’s a new market to them.

You’ll need to educate them on why this category matters and what’s your to win here.

They know the market extremely well and have strong opinions.

You’ll spend more time unpacking their assumptions than pitching your own.

They know the market and are already excited about it.

You’ll do the least amount of convincing here.

Fundraising is almost always easier with investors in bucket 1 or bucket 3. Investors in bucket 2 aren’t impossible to convince—I’ve personally changed my mind because a founder proved to me something I missed, but it requires more friction and patience. This is the origin of the classic “strong opinions, loosely held” slogan.

In the earliest stages of company building, most of what you believe will be understood as a hypothesis. If you are raising venture capital, your job is also to find the investors who see the world the way you do or are at least willing to stretch their imagination alongside yours. In a market this competitive, that alignment is harder than ever to find, but still should be a north star.

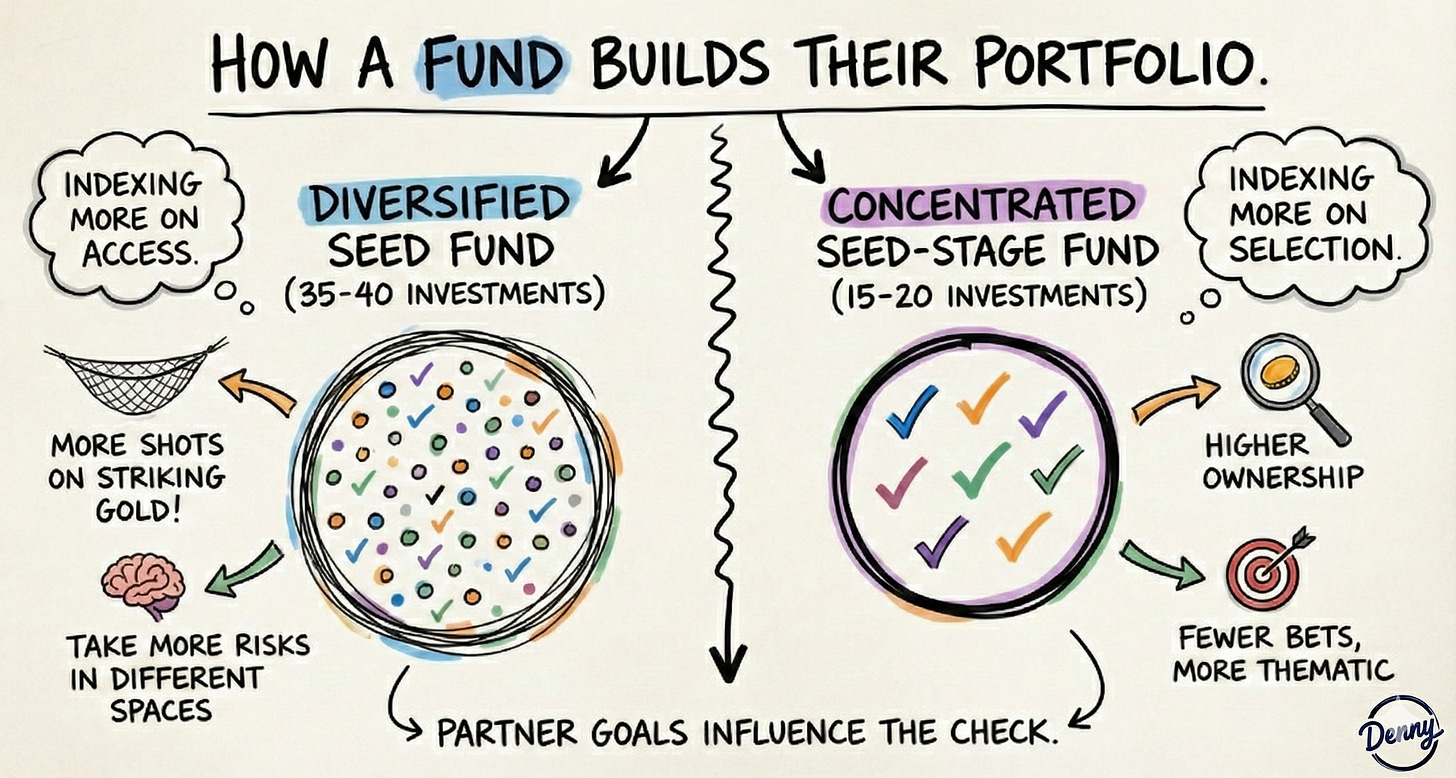

Last thing to think about is how a fund builds their portfolio. Even if some funds are competing in the same pond, their partners may have different goals in practice. These goals influence how they decide to write a check. For example, think about 2 seed stage funds that are the same fund size but focus on different levels of portfolio concentration:

A letter to investors:

Seed-stage investing is ultimately the business of indexing on N of 1 people. Founders are trying to solve problems that are brutally hard and, if they succeed, massively pay off. There are many ways to “win deals” but the durable way is to show up, serve people, and stay top of mind.

Ho Nam from Altos Ventures(who’s been around since 1998) has said that even great investors may only have 1 or 2 true outliers in their entire career. Because of the power law, those few companies can dwarf the returns from everything else. The mission in this business is to find those legendary teams, engage deeply, and partner with them for decades. One thing I’ve learned in the last 2 years is that your impact is not limited to the founders you invest in. You can intro any founder to a customer. Connect them to the right co-investor. Help them unblock a problem they’re hitting. Those moments compound. Ultimately, you continuously have to solve how to allocate your time with ambitious people in your own way.

There have been many times I didn’t invest in a founder but helped them anyway simply because I was curious about what they were building. Those founders tend to come back. Either with founder referrals, with their friends, or with themselves in the next round. That’s the part people underestimate. In venture, your reputation is the whole game; It compounds just like great companies do! And it’s one of the few things entirely in your control in a business of so much uncertainty and long timelines.

Really sharp framing of the current dynamics. The observation that taste has become the scarce resource in a capital abundant environment is something more founders need to internalize. It explains why we're seeing this bimodal distribution in valuations where the top decile commands premiums that would have been unthinkable three years ago while the middle gets squeezed. The pivot case studies are particularly valuable context here since they remind us that the path to outlier status is rarely linear, and the teams surviving the current bridge round enviornment might emerge with exactly the kind of battle tested judgment investors should be looking for.

Great piece Denny!